OVERVIEW

Multiplace evolved from a design research project I embarked on at The University of Sydney, into a product I’ve started to build with some developer friends.

I came across a university course called ‘Everyday Digital Media’ (ARIN2620), where I first realised the degree of consideration and thought that goes into managing and shaping who we are online. I felt that if I was able to figure out a way to provide value, or solve some of the pain points that people experience when presenting themselves online, that I would have a great idea.

The following semester, I began to research this problem area and develop solutions over 2 design courses (DECO2019 & DECO2102), before getting started on an MVP.

ROLES/SKILLS

TOOLS

User research, UX/UI Design, Prototyping, Usability testing

Figma, Dovetail, Balsamiq, Adobe Illustrator, Miro

PERIOD

TEAM

Jul 2023 – Nov 2023

Farhan Khan (Myself), Aamir Aye

GRADES

DECO2019 – 87 (HD), DECO2102 – 93 (HD)

ATTENTION ⚠️

I’m continuing to publish content to this page as this was quite a big project. Expect even more hi-fi screens and features to the prototype as well as ‘more details’ toggles over the coming days and weeks.

Please note that not all details surrounding this product will be shown publicly. This includes the fully functional prototype showcasing some core features. Please contact me if you would like a complete brief surrounding all the features of Multiplace.

In the meantime, please read ahead. Most of my process is there 🙂

What is Multiplace?

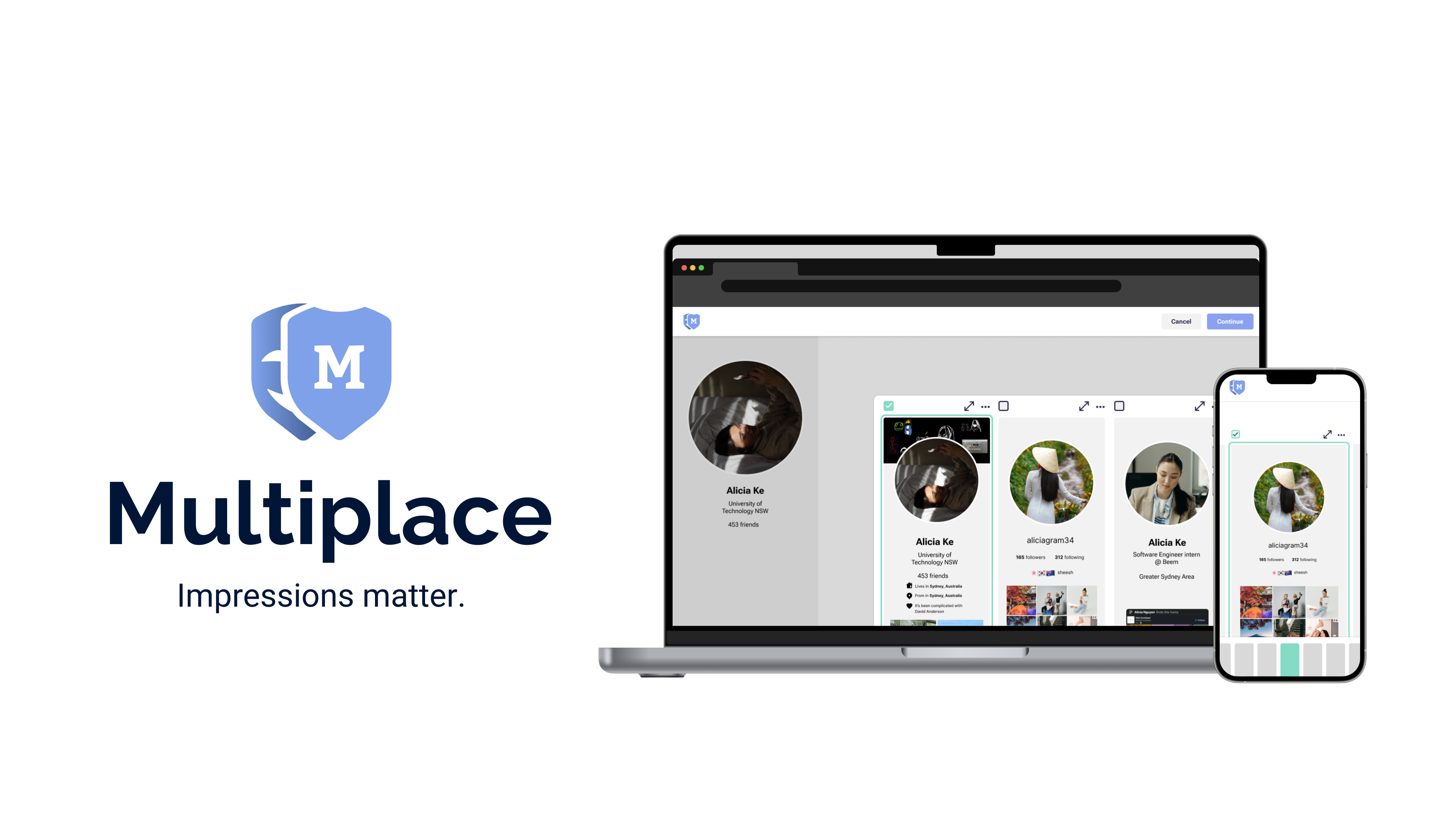

Multiplace is a platform where you can ask others what they think of your social media profiles.

That is the most simple way to put it. In this platform, people all over the world can give you feedback in regard to all your social media profiles. We all present ourselves online across various social network platforms, in a way which communicates things about ourselves. So, how do we know what we’re putting out there is aligned with how we want to be perceived?

Receiving feedback from people about your online identity gives the sharer the affirmation that they are presenting themselves how they want to be perceived.

How it works?

1. Create mock versions of your online identities (Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn and other), retrieved easily through APIs upon sign-up. You can make further edits if things aren’t quite right.

2. Once edited, select the identities you want to share so you can get feedback on the kind of impression you give off. You can filter the kind of audience who sees your request.

3. Post your listing, and provide feedback on the requests made by other people all over the world who are curious about their own impression. You might resemble the people who are in their lives.

4. Take a close look at each request, and understand what the other person is trying to achieve. How well do they fare based on their objectives?

So how did I end up with Multiplace, and what problem does it solve? ⬇️⬇️⬇️⬇️

Discover

Introduction

We live in an unprecedented time of connectedness and visibility. Every fragment of digital information from user names and profile pictures, to typing styles and the posts we engage with are used to make an assessment about who we are. [Trottier, 2013]

As newer, sophisticated media continues to emerge, the cues which communicate information about someone evolves with it. In our attempts to project (or withhold) who we are, our messages may be misinterpreted or recontextualised as the cultures and meanings behind how we present ourselves online are rarely defined, and quickly evolving.

Because there is so much uncertainty and ambiguity surrounding this area, this research project aims to explore some of the challenges that young people face in managing who they are online. Many young people have come of age in a world where their identities are integrated with their presence online, having adopted technologies and profiles from ages much earlier than the generations before them. Whilst there is considerable research exploring the phenomena of identity construction and management, there is a need to revisit it as the number of platforms and their sophistication are at an all time high, and the unique experiences of generation Z in particular is relatively unexplored.

The Problem

People struggle in presenting themselves online, as they hold many public identities across different platforms, which are seen by different audiences.

Existing Research

This is where I see what’s already known about this area, so I don’t end up researching something that someone already has done. This helps me understand the problem area better, but it also determines the angle I take with my own research.

I sifted through many studies, as well as theories devised by sociologists and identity theorists from their study and analysis of behaviours online.

1/2 - Multiplicity of Identity and Social Media Practices

“A woman wakes up as a lover, makes breakfast as a mother, and drives to work as a lawyer”

– Sherry Turkle, 1997

Multiplicity of Identity & Social Media Practices

Identity theory, particularly the work of Erving Goffman (1959) has concluded the notion of the self being malleable and varied, instead of rigid and unchanging. Depending on the context, people will vary their self-presentation, and sociologist Sherry Turkle (1997) provides a great example of this where “a woman wakes up as a lover, makes breakfast as a mother, and drives to work as a lawyer”. While many anecdotal experiences affirm this multiplicity of identity through various ‘selves’ being represented across different social media platforms, the implications of having many ‘selves’ to one’s online identity invites further research. The literature mostly revolves around how individuals may engage in “digital identity and impression management” (Veletsianos, 2013) in particular platforms or by particular users.

The construction of one’s online identity falls to the fields and affordances that a social media platform allows customisation for (Marwick, 2013), and the artifacts left behind by users serve as “symbolic markers” of that person’s identity (Papacharissi, 2002). Individualising and distinguishing oneself is a strong motivation for users (Baym, 2010). Considering this, studies in the past have uncovered patterns of perception people have when forming an impression of themselves, particularly on Facebook. In a study by Young (2013), it was found that behaviors such as sharing status updates, posting paragraphs and joining groups and pages are usually done by users with goals of projecting certain aspects of oneself or to make a statement, and these cues are interpreted in specific, patterned ways by audiences.

Other studies may explore the practices of specific groups of people, as was the case in Veletsianos’ study (2013) where the social media practices of scholars were described. While the methods and implications of online identity construction have been explored for specific platforms, studies fail to explore them more broadly, outside of the confines of a single platform. How people design each of their ‘selves’ – professional, non-professional and other amongst many platforms are worth investigating in a world which is more networked than ever. This is more imperative when the architecture of many popular social media platforms have undergone various changes.

Erving Goffman (1956) explored the notion of identity having multiplicity. The version of ourselves we present to our manager, is probably quite different to the version we present to our partner or crush. When you’re out with mates killing time on a weekend and you bump into your boss, your behaviour changes.

Who we are at work, is different to we are at home – and that’s different to who we are at a social gathering. Depending on the context and audience, we change how we behave and interact with others.

While many anecdotal experiences affirm this multiplicity of identity through various ‘selves’ being represented across different social media platforms, the implications of having many ‘selves’ to one’s online identity invites further research.

Existing Research…

- Mostly revolves around certain kinds of users such as academics or scholars (such as in a study by Veletsianos, 2013).

- Fails to analyse and distinguish behaviour beyond particular platforms such as Facebook, and explore the relationship between these different platforms.

Our Research needs to…

- Focus on Gen Z mainly, and people more broadly – not just scholars or particular kinds of social media users.

- Look beyond one platform. Study how identity shifts between different platforms.

2/2 - Surveillance, Privacy and Context Collapse

“Social media are sites of struggle between users, employers and platform owners to control online identities” – José van Djick, 2013

Surveillance, Privacy & Context Collapse

In today’s heavily networked society, there is a newfound visibility of one’s identity, and with it a constant feeling of surveillance. People create their identities to be seen by others (boyd, 2010). Context collapse is a prevalent issue, where all the audiences who were once segregated in offline contexts, can now view our professional and non-professional selves (Marwick and boyd 2011a). Existing studies have shown that many of our self-presentations online are done so with consideration of the various audiences who view them. As described by Dijck (2013), social media platforms are “sites of struggle between users, employers and platform owners to control online identities”.

There is a ‘burden’ in managing oneself on a platform when both professional and non-professional networks are present (DiMicco, Millen, 2007). DiMicco’s study showed that Facebook users tend to become very conscious of their self-presentation once they connect with more people from their professional lives, shifting their presentation and behaviour on the platform considerably.

Whilst there might seem to be a trade-off between privacy and trust when presenting oneself, for younger people, social expectations of privacy protection has made the concerns surrounding self-presentation to be what is “fitting to reveal” (Durante, 2011). Digital natives are responsible for creating the online “contexts of communication” through social networking during their upbringing, and so they may have ‘particular expectations of privacy protection’. A study by Bullingham (2013) affirms this idea, suggesting that anonymising can be a subtle form of persona adoption as there are external pressures to do so. There is opportunity to further understand how young people design identities, particularly what they believe their audience is seeing. How privacy and surveillance influence the construction of identities invites further research, particularly for younger users whose identities are embedded with these platforms from a very young age.

In the ‘real’ world, our audiences are segregated. Our managers really only see us at work, our gym mates at the gym, the soccer moms only on Saturday mornings, your crush only for that one unit of study. In the online world, all these audiences converge. Everyone has access to any public presentation of ours, any time of the week.

Our professional audiences, if they are truly bothered, may gain access to our more personal and social selves through Facebook and Instagram. If they took the extra step to befriend or follow us on these platforms, then what version of ourselves do we perform? Professional, social or private?

Existing Research says…

- Inviting professional people as friends on Facebook makes managing one’s identity/impression difficult

- There are social expectations of privacy protection i.e. there is peer pressure to be private – it is unusual NOT to be to some degree private. Some things are ‘fitting to reveal’ as there are ‘particular expectations of privacy protection’ (Durante, 2011), (Bullingham, 2013)

Our Research aims to…

- Explain this ‘burden’ or difficulty of managing one’s impression online. Why is it difficult?

- Discover the social expectations or cultures of privacy protection and performance which exist across ALL platforms.

Research Objective

As the phenomena of online identity management is laced with various influencing factors and personal motivations, the goal of this research is to describe the challenges Generations Y and Z face in managing their online identities. This study defines young people as Generations Y and Z, and of ages between 18 and 40.

This study aims to answer the following research questions in order to meet the aforementioned goal:

- What are the goals and motivations of young people when creating online identities?

- What is getting in the way of these goals?

- How do people vary their self-presentations across social media platforms?

- What is the relationship between each of the profiles one has online?

- How does surveillance affect the construction of online identities for young people?

- How conscious are young people about their audiences and how they may be perceived?

Research Methodology

I took a triangulated approach to my research (i.e. I used multiple research methods/data sources to validate my data – if it’s consistent across different methods, it’s reliable data).

Triangulated approaches allow researchers to test the validity of qualitative data through the comparison of information from different sources and by deriving insights from shared trends, attitudes and behaviour (Carter et al, 2014). It also results in a richer understanding of the problem area.

Sensitising Materials

Sensitising materials serve to instill self-reflection and expression prior to the generative exercises, to induce richer information during the generative sessions themselves (Visser, et al., 2005).

Asking our users to complete some tasks up to a week before an interview or workshop can get them thinking about their experiences managing their online identities. We aimed to include 2 – 3 sensitising activities for our participants.

Interviews

Talking to our users.

Interviews help gather concrete information about existing experiences, rather than speculation about future products or situations (Tomitsch et al, 2018). They also allow for a comprehensive understanding of personal experiences and perspectives (Carter et al, 2014).

A semi-structured interview format involving 5-8 participants with young adults was followed. A semi-structured approach allows for more flexibility and specificity to probe into the unique practices some participants may describe, allowing us to discover novel insights in our generative research (Tomitsch et al, 2018).

Workshops

Focus groups have received criticism as creating an artificial environment which bears no resemblance to the context being researched or designed for. Social desirability bias, Group think and Anchoring are some common issues when asking users about their experiences in a group environment.

That being said, workshops can allow research teams to obtain ‘deeper levels of knowledge’ (Visser, et al., 2005) than standard interviews, through the creation of visual artifacts which foster discussion.

I employed the Generative Dialogue Framework (GDF) created by Dimitrakopoulou, an approach which allows participants to “surface their perceptions and mental models”. This approach uncovers their lived experiences without facing many of the drawbacks that traditional focus groups face such as social desirability biases and any inequities amongst participant expressions.

Interview data was to be supplemented with these deeper, latent insights gathered through more generative and experiential activities of a workshop (Dimitrakopoulou, 2021).

Define

Findings & Insights

Insight 1/3: The online world is a unique opportunity

What we found in our research (finding):

Young people project a certain image, statement or aspect about themselves through their online identities, and are very conscious about each cue and its implications.

Why? (insight) ✨

Young people see that the unique affordances and cues provided by online platforms are an opportunity to communicate and express aspects of themselves in ways they cannot offline.

A social media platform is a static representation of oneself which can be shaped with great autonomy and ease. Users of these platforms are empowered to present themself however they like within the confines of the site’s affordances.

The various functions and behaviours that a social media platform enables can be deliberated and wielded in ways that offline behaviours cannot. These include uploading display pictures, joining groups, following people and pages, typing in different ways, posting content (and how frequently one posts) amongst many other behaviours which the user can choose and scale to their liking. Baym’s 2010 study had suggested that a strong motivation for users was to individualise and distinguish themselves. Our research shows that a uniquely versatile online identity construction is what enables and influences young people to practice this motivation.

Young people understand that many of the behaviours they show online can be analysed and interpreted. As a result, it creates a heightened awareness and consciousness in users as to how they should use the affordances and features of a platform to manage their identity. Through careful consideration of how one should use the tools available on a platform, users will project, communicate or emphasize something about who they are. Our research builds on Marwick’s claim (2013) of identity construction falling to the affordances of a social media platform, now revealing that young people see value in the affordances as an opportunity enabling them to emphasise and communicate aspects of their identity in ways impossible without them.

One participant explained how wearing an Islamic cap in his LinkedIn display picture was intentional, so that he could communicate to his audience that one can embrace their faith in public, not compromise and still do well in their career. Whilst he doesn’t wear this religious symbol outside of work, he feels that he should “project it more” in “foreign” contexts like his workplace, which also includes foreign online contexts such as his LinkedIn profile where this message is broadcasted to his younger audience that he wants to inspire. This is enabled by a platform like LinkedIn, which makes it easy for users to communicate their work history, achievements and success – things which can only be emphasised within specific situations and contexts in the ‘real’ world.

Insight 2/3: The online world reflects the offline

What we found in our research (finding):

Young people’s identities across platforms are a reflection of real-life contexts, falling to the affordances and cues which best represent that context.

Why? (insight) ✨

Young people’s identities on platforms reflect real-life contexts because they see each platform as a virtual representation of that offline place. Consequently, their behaviours and self-presentations resemble how they believe one should present themself in such a context.

In seeing each platform as resembling an offline context, the user’s self-presentation and behaviour platform to platform varies just as it does in ‘real life’. This suggests a translation of Erving Goffman’s (1959) theory of the multiplicity of identity into online contexts as well. As a result, young people see each social media platform as having a purpose, and therefore dedicated use-cases. Aspects of one’s ‘real’ identity would be presented across these different platforms, based on that use-case or what they would consider to be appropriate for the platform. This is consistent with Durante’s 2011 study regarding the social expectations of privacy protection, and how users would share what is “fitting to reveal”, but our research suggests that meeting social expectations is practiced more broadly, not just when one is making themself private.

It was understood that there are certain cultures behind how a platform should typically be used, and this expectation would influence people to adhere to general practices for platforms. This was the case with the stories function in Facebook which young people mentioned they didn’t use, because “people haven’t taken a liking” to it, and “no one really uses Facebook stories”. Young people mentioned how “expectation” and “what’s more accepted” strongly guided their kinds of interaction on different platforms.

This extends from Bullingham’s (2013) findings of societal pressures to conform and fit in to embellished avatar designs in online game ‘Second Life’ despite preceding motivations to present a version more closely resembling their non-virtual self. We now know that this phenomena occurs in all platforms, and users will form a common understanding that platforms or features are meant to be used a certain way. Regardless of what young people may intend to present, they will naturally incline towards certain guidelines upon observing how others use the platform.

Insight 3/3: The importance of impression management

What we found in our research (finding):

Young people are conscious of unwanted content becoming visible to certain audiences through inter-platform surveillance, and they consider this when presenting themselves on public platforms.

Why? (insight) ✨

Young people are conscious of inter-platform surveillance because they want to maintain certain impressions with their many audiences.

Impression management is a strong priority for young people online. Many of them consider whether any given self-presentation violates the impression they want to give (or already have) with the diversity of their viewers. As a result, the identities people portray regardless of the platform’s context are often done considering that different kinds of people, close and distant, can view them.

Our research uncovered an example where an Instagram user would be careful of what he posts due to his involvement with a church, so images in a bar or with alcohol are filtered out to maintain a positive impression with audiences from his youth program. This is consistent with boyd’s (2010) analysis of profiles as being “actively and consciously” crafted to be “seen by others”.

According to boyd, it is not uncommon for people to create a “narrower public” by limiting the visibility of profiles to some degree to comfortably portray withheld behaviours such as the ones described by the participant earlier. Interestingly, our research also revealed that for young people, it wouldn’t be entirely problematic if distant or professional audiences were to view more social and recreational sides of one’s identity, as they would understand that “people have personalities and personal lives” and that they had “factored that possibility into the development of (their) identity across both platforms”.

This suggests an evolution from boyd’s study in the cultures of online identity and social media, where even some profiles designed for a ‘narrower public’ are now done considering that they may be surveyed by ‘unideal’ audiences. Additionally, it suggests a shift in online culture where audiences are more accepting of people’s more private and social selves being on display, which earlier online cultures may have deemed inappropriate. A participant also mentioned that shifts in work culture towards flexible work and allowing casual clothing from previously having to “act professional” makes him not worry about broader audiences visiting his Instagram.

This is a strong adjustment since the ‘burden’ of identity management in DiMicco’s 2007 study where Facebook users had a difficult time managing their identity. People are now employing various measures including narrowing their publics through private profiles, close friends lists on Instagram and other methods alongside this culture shift.

Design Considerations

In order to generate design solutions which respond to the research, Aamir and I thought about the features which our ideas should aim to have. From our 3 insights, we extracted the goals of our users in managing their many online identitites scattered across various platforms.

For a great product, how might we...

HMW #1

Help our users in effectively communicating the things about themselves which they want to express?

HMW #2

Help our users understand what is relevant or best to perform in a given social media platform?

HMW #3

Help our users to build & maintain certain impressions amongst their many different audiences?

We kept these design considerations in mind as we ideated concepts, judging the quality of our solutions based on how well they responded to each HMW statement.

Develop

Ideation

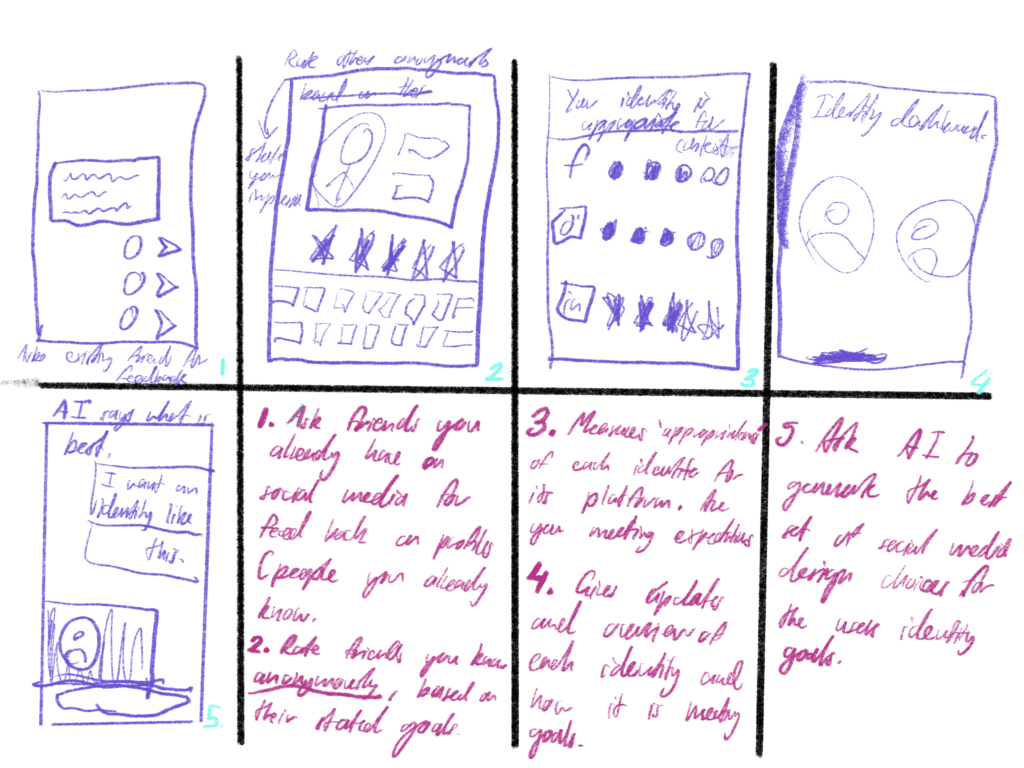

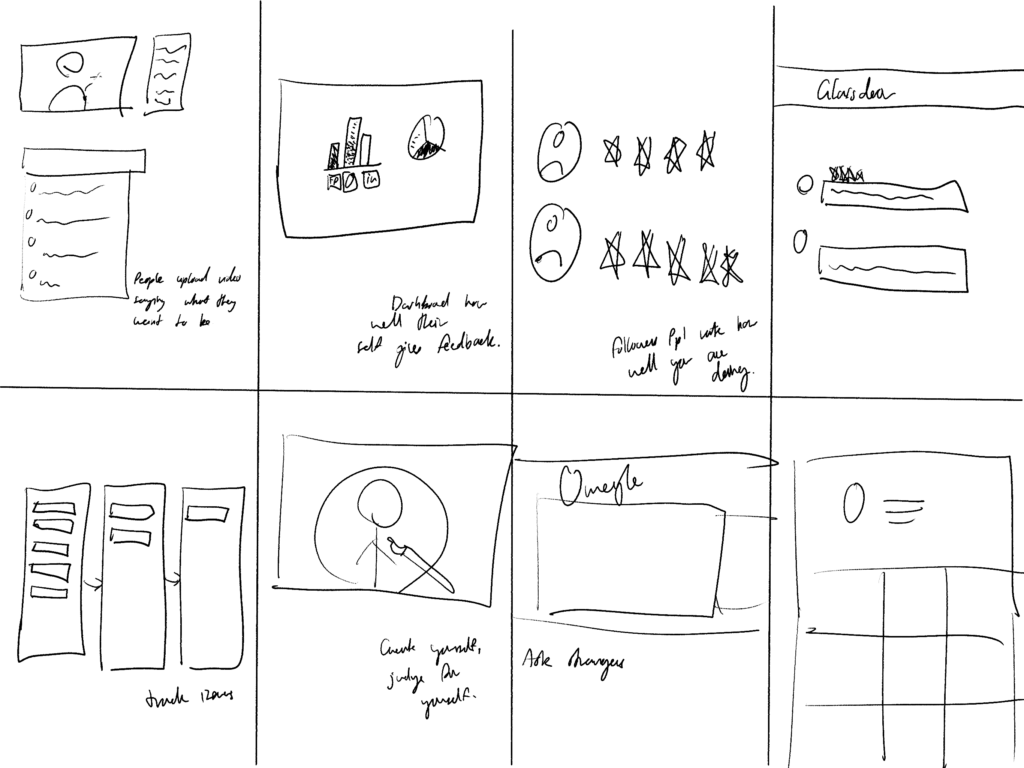

Using forced association and some crazy 8’s, we generated over 60 ideas which responded to the research. Aamir and I used decision matrices to rate our solutions and filter out the ideas which we deemed to be less effective solutions. We did some mixing and matching for our ideas before we came up with Multiplace.

Our forced association included key words such as chatroom, editor, messenger, pinboard, playlist and other prominent, well-known social media features, as well as work-related key words such as kanban, issue-tracking and documentation.

Since we wanted to settle for a screen-based interface, we tried to make our concepts employ common information architecture patterns.

Filtering down to ‘Multiplace’

A concept which rated extremely well for the first two design principles we defined earlier, was the idea of asking friends online what they felt about one’s existing or potential social media site. After all, as designers, we know that talking to your users is the best way to test something.

Despite its success in providing accurate feedback, the downside is that it rates poorly in principle 3. Impression management is important, so asking people who are part of your true, real-life audience what they might think of your profiles could harm your own image.

However, providing the opportunity to anonymise oneself through asking strangers who are similar to your audiences could solve this issue. With strangers, there is no offline relationship, and there are little to no stakes. The relationship is purely dedicated for the use-case of providing feedback. There is research suggesting that online, “seperation, time lags and sparse cues remove social pressures of lying” (Baym, 2010). Self-anxious people in particular felt they were more likely to express themself online, and not having to face people immediately, known or unknown tends to lead to more honesty (Rainie, Lenhart, Fox, Spooner, & Horrigan, 2000).

“In the end, then, people can and do develop meaningful personal relationships online. Many of them remain weak and specialized, used to exchange resources around a fairly narrow set of topics of shared interest. These relationships make important contributions to people’s lives, especially when they allow people to interact about interests and concerns that their close relational partners do not share.”

– Nancy Baym (2010)

How ‘Multiplace’ responds to the research

How might we…

In Multiplace…

HMW #1

Help our users in effectively communicating the things about themselves which they want to express?

Users can verify whether a certain self-presentation best communicates what they intend, by sharing and asking others

HMW #2

Help our users understand what is relevant or best to perform in a given social media platform?

Asking others allows the user to understand what others think about performing a certain way, on a certain platform

HMW #3

Help our users to build & maintain certain impressions amongst their many different audiences?

You can share your ‘selves’ to similar audiences in Multiplace, and guage their impression to check whether a certain performance is safe.

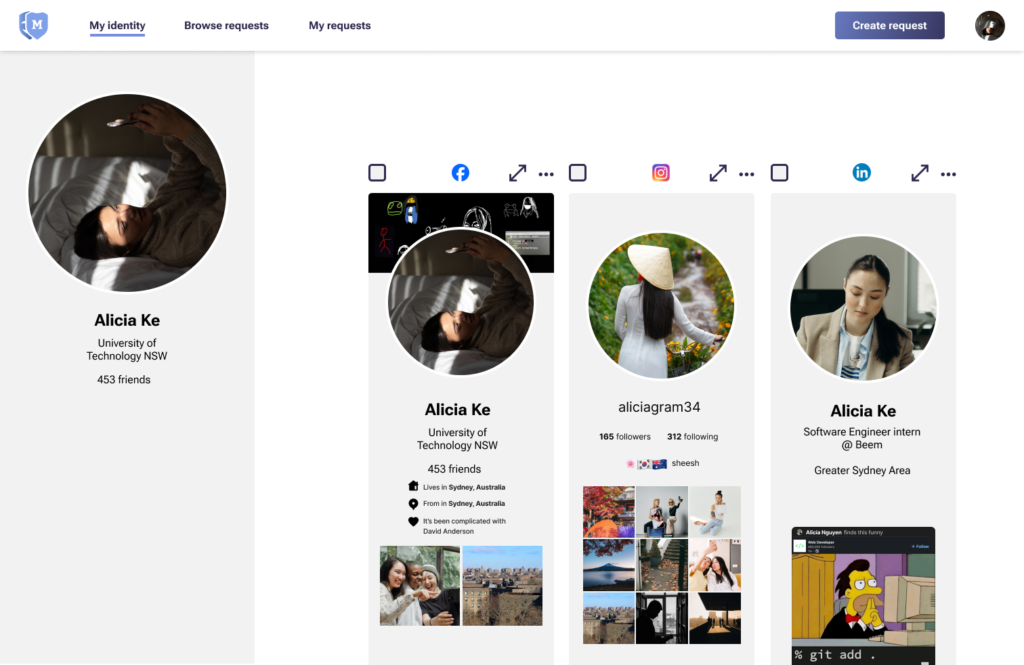

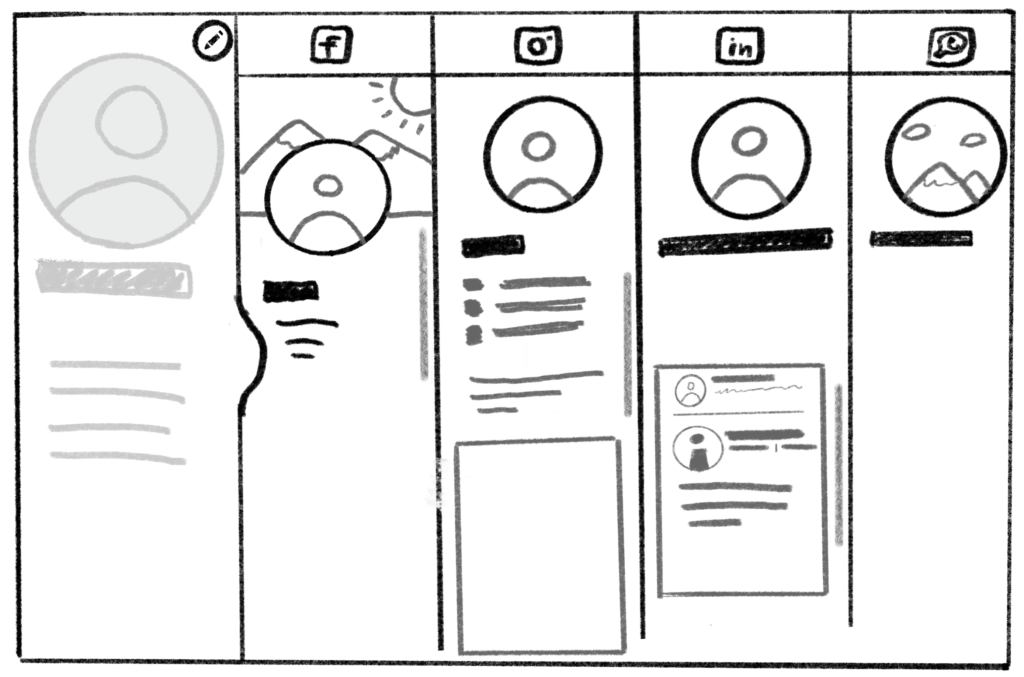

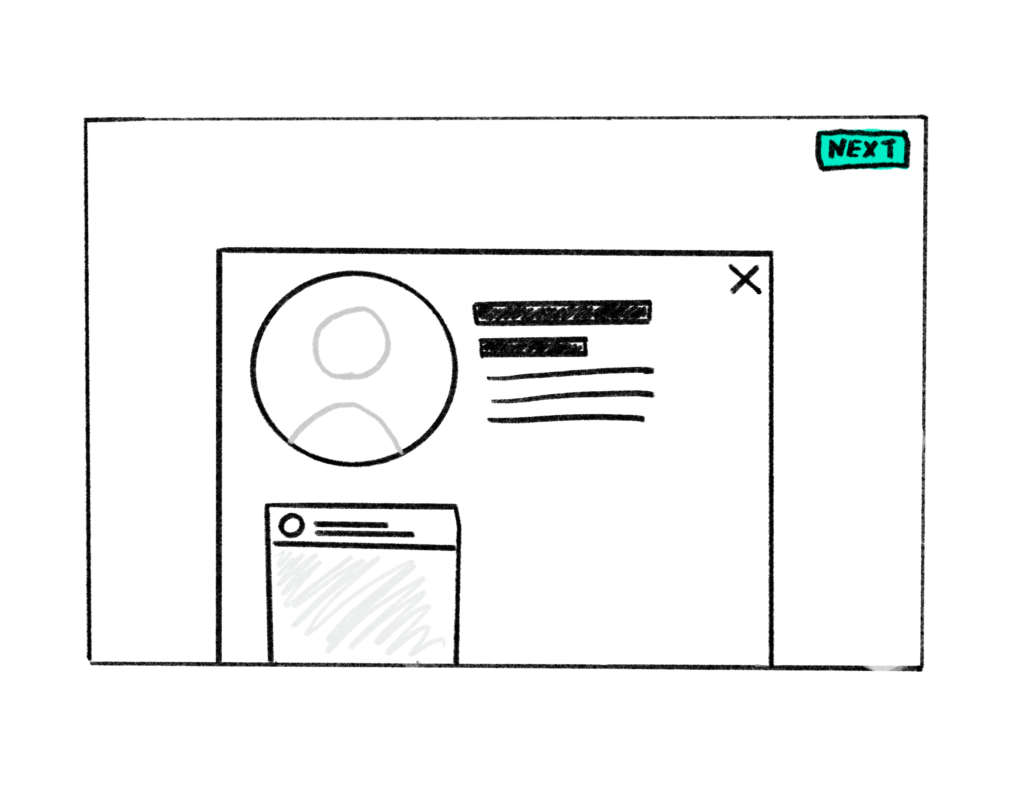

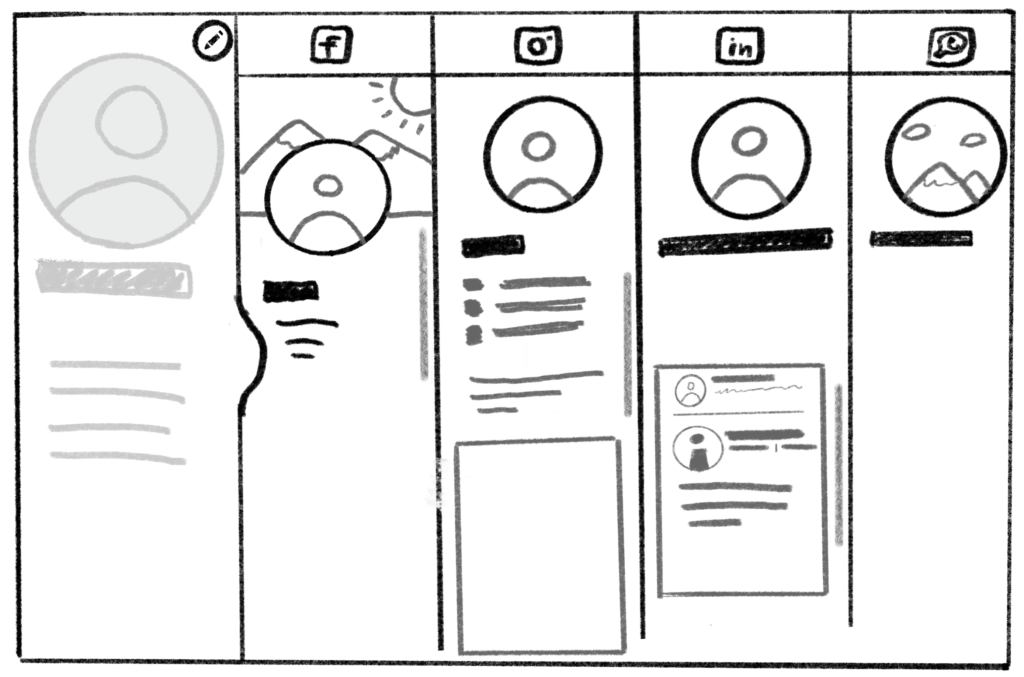

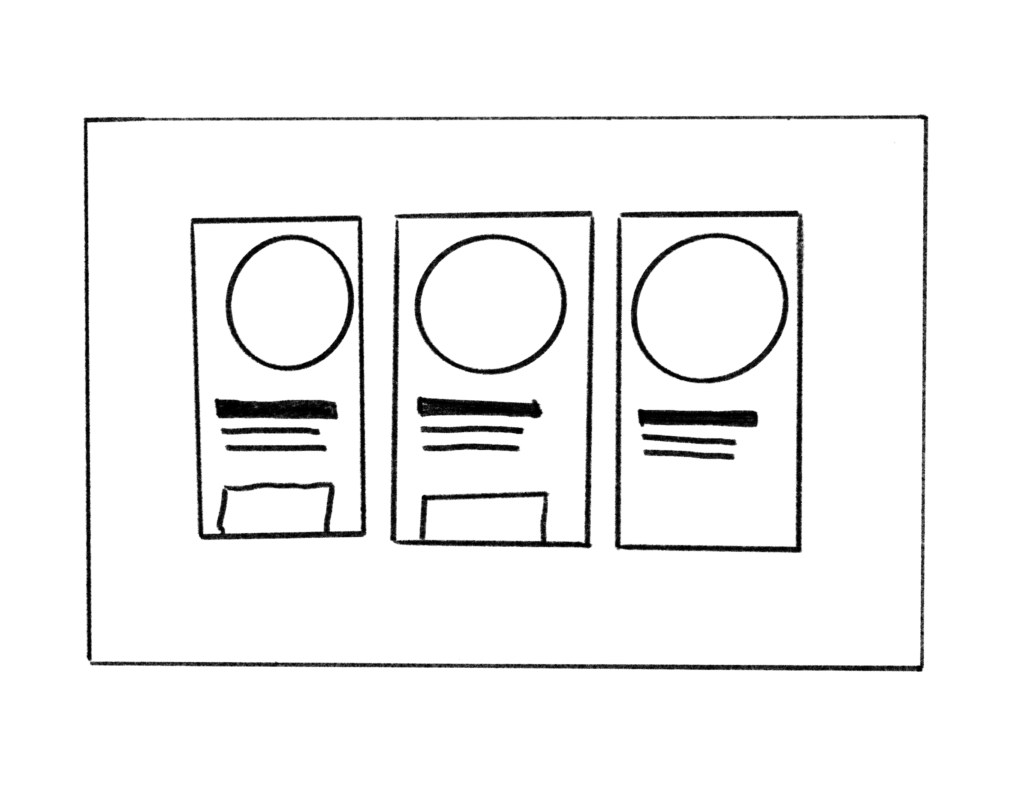

Core Function 1: Wardrobe

Multiplace’s primary interface is called the ‘wardrobe’, shown below. It organises each of the users social media profiles, blogs or other ‘selves’ as columns stacked next to each other. This provides a birds-eye view of one’s overall identity, allowing the user to compare their ‘selves’ and obtain an idea of the impression they may be giving off to their audiences.

Core Function 2: Mock-editing

Users can make create mock changes to their existing profiles and evaluate how effective they are for themselves, or share it to the broader community for others to evaluate. They are free to make those changes in their real social media profiles later if they like, once they have received feedback.

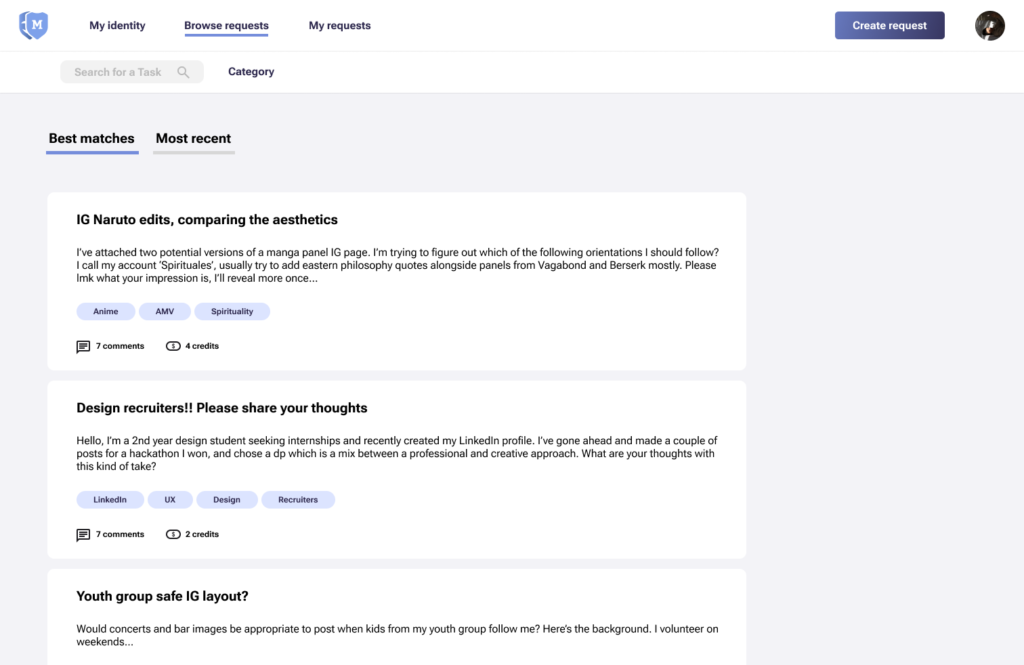

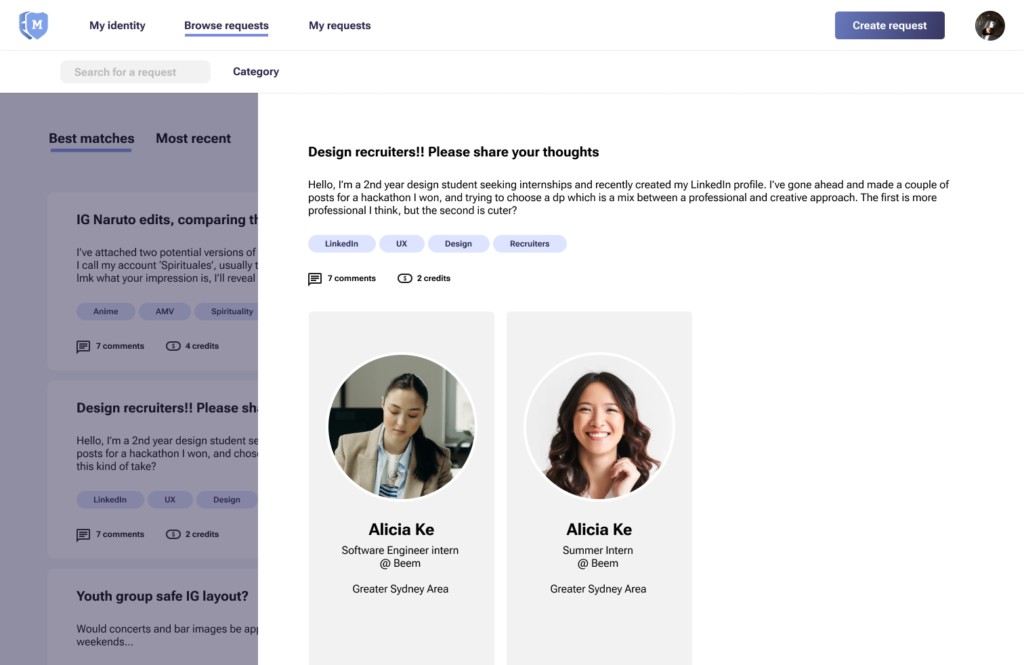

Core Function 3: Community Sharing

Multiplace allows users to share a selection of their identities publicly for others to inform how they percieve the user based on the shared data.

Evaluative Research Approach

We planned 2 rounds of testing, which means 3 iterations of Multiplace.

In each round, we will have:

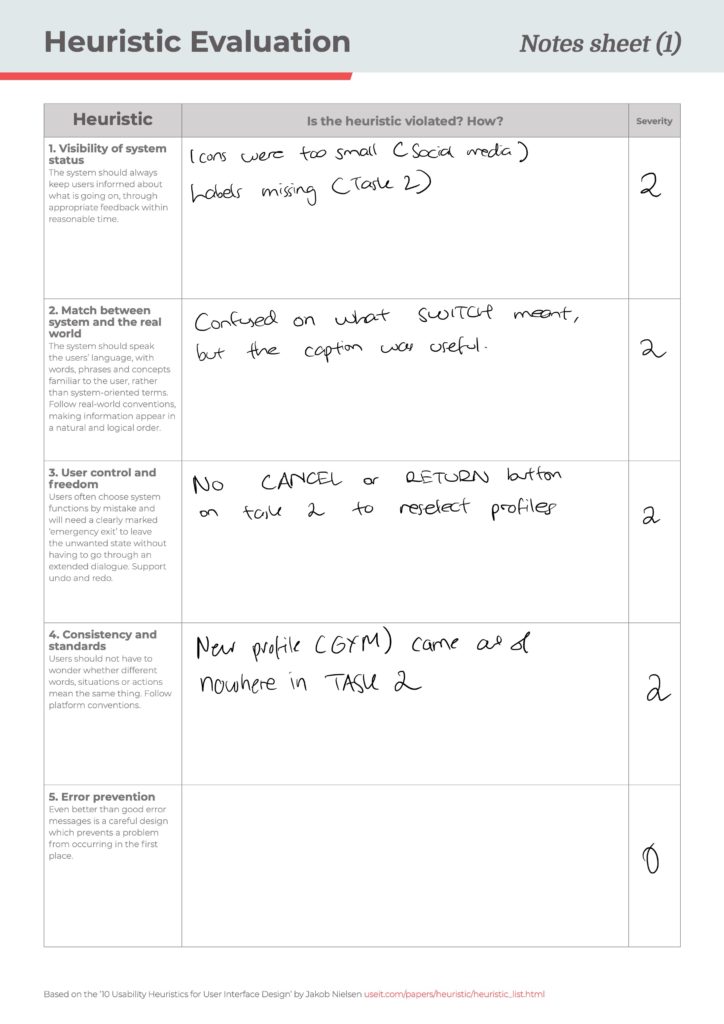

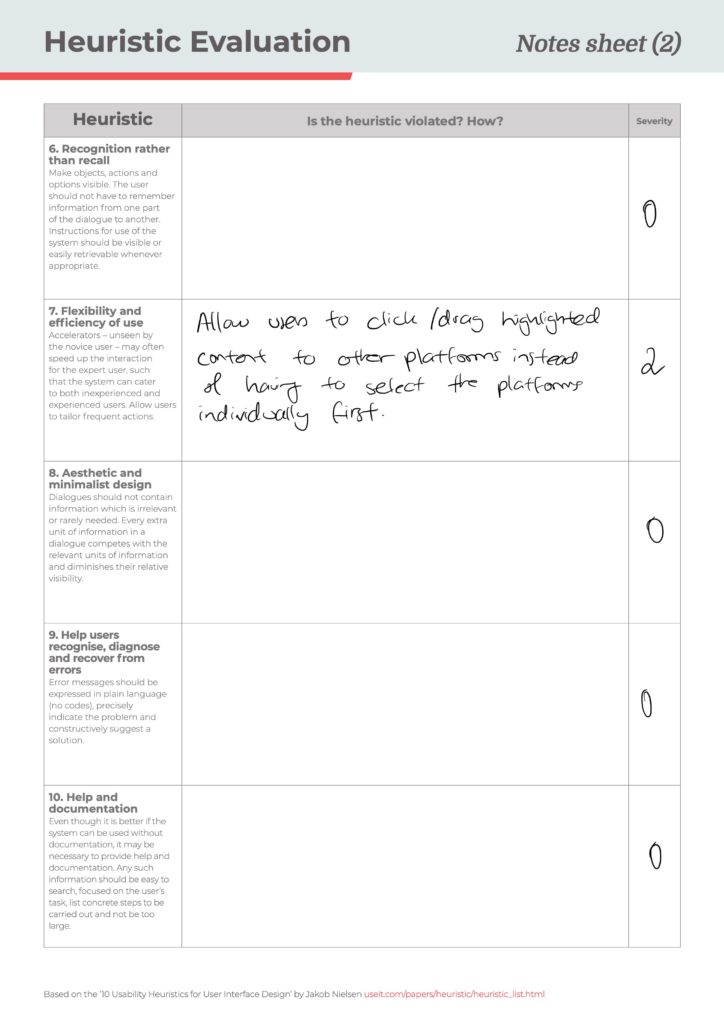

- 2 – 3 Heurestic evaluations (HE)

- 4 – 5 Usability tests

Heurestic evaluations are an effective tool for collecting early feedback at a low cost, time-efficient manner (Tomitsch et. al 2018). Students studying Design and Architecture as well asindividuals with industry experience were selected for this kind of evaluation as this methodcollects feedback from experts in particular who may recognise potential problems, and successdepends heavily on the knowledge of the experts and their familiarity with heurestics (Tomitsh etal 2018). Even feedback from a single expert reviewer can filter out 35% of usability problems.

Despite their merit, according to Lauesen (2005), this method has a 50% chance of reporting falseproblems during more early stages of prototyping. As a result, supplementing this method withUsability tests can help uncover ‘real’ problems, despite being higher effort. Usability testsmeasure the success target users have with our design. It reveals the degree to which the usersmental model matches the conceptual model, and allows us to implement changes in the nextiteration for a more usable design (Tomistch et. al 2018)

HE protocol

HE’s were completed only with those familiar with Jakob Nielson’s 10 heurestics or similar so that they know how well this iteration fares for each heuristic. This would include design students or those with experience in the industry.

Usability testing protocol

We tested how well our prototype did in enabling users to complete relevant tasks. Participants were asked to think aloud as they completed these tasks, and any verbal protocol or beheviour was recorded. These tasks are some of the core features of the Multiplace product:

Task #1

Add your Facebook, IG and LinkedIn profiles or other ‘online identities’ onto Multiplace.

Task #2

Edit your LinkedIn account and change the kinds of posts that you are engaging with. Then, share ONLY your LinkedIn and Facebook profiles to the public to get feedback.

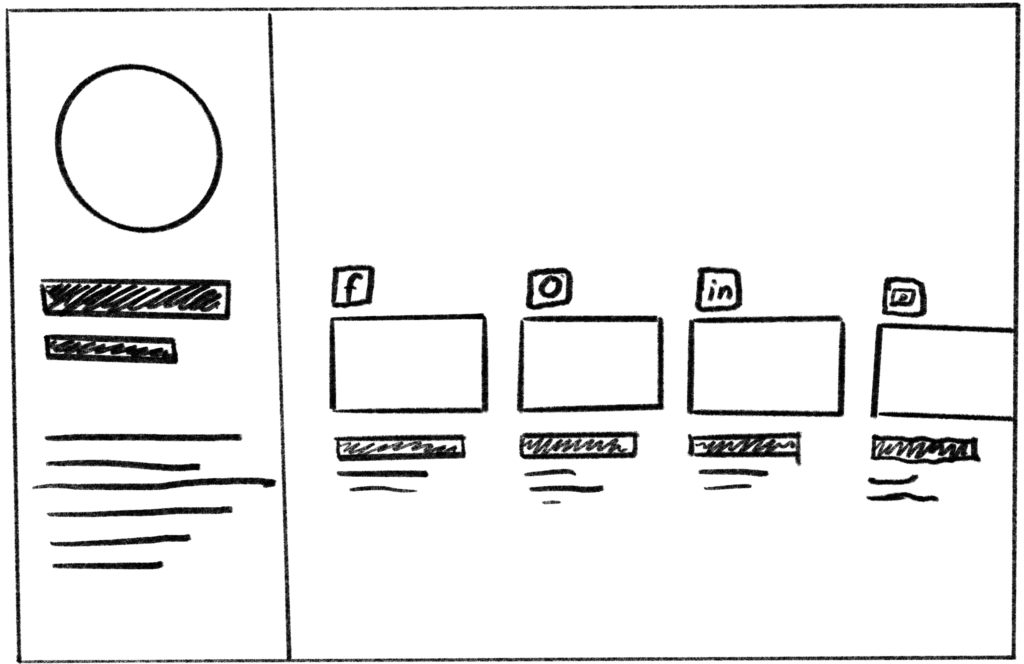

Iteration 1/3: Paper prototypes -> Wireframes

Aamir and I worked on the first set of paper prototypes to assess the effectiveness of some essential screens of the concept, and once we felt it would be effective, created a wireflow. We did this first because we felt much of Multiplace’s success hinged on how users would be able to derive value about their identity. We needed to be innovative in the way our screens were designed, this was a very new territory. Once we had created the ‘Wardrobe’ screens, we sketched screens for each step of the wireflow.

Improving ‘Wardrobe’ function

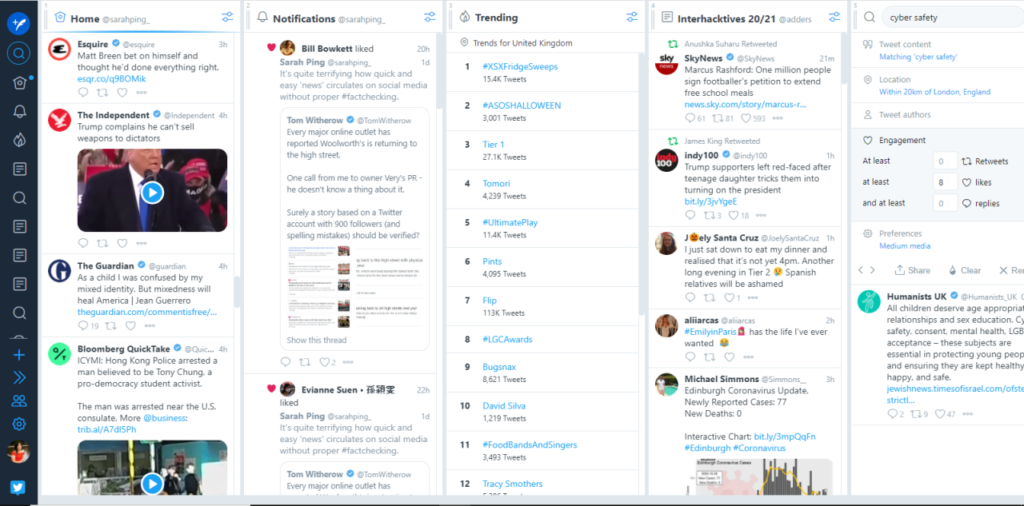

For the ‘Wardrobe’ function, I implemented ‘many workspaces’ information architecture pattern, which is used in other popular software such as TweetDeck, shown below. This pattern takes a multipanel/multistream approach.

The first draft of the main ‘Wardrobe’ screen, shown on the bottom left employed a ‘dashboard’ and ‘thumbnail grid’ patterns, before settling for the ‘many workspaces’ pattern on the bottom right.

Many information architecture patterns were experimented with when designing what I came to call the ’Wardrobe’. The goal of the screen was to find a way to provide more clarity to the user about how their self-presentations online are shaping their identity. This means it would have to communicate information across all of one’s social media profiles.

The first sketch took influence from dashboard and thumbnail grid patterns. Dashboards allow for a quick update on status by providing users with any actionable information, charts, graphs,metrics and other immediate pieces of key, relevant information (Tidwell, 2010).

The appeal behind dashboard set ups are the immediate value which it can provide a user. However, in the context of online identities, getting an overview or assessment on one’s identity isn’t so easy. How a collection of self-presentations are perceived is a very subjective matter which can be difficult to represent, as dashboards often work with quantitative information represented through graphs, charts and percentages.

In a following iteration, the ‘Many Workspaces’ pattern was implemented instead, as the opportunity to view multiple ‘selves’ at once could allow for a birds-eye view of one’s overall presentation. Instead of having to display objective data in the form of metrics, this allows the user to judge their own profiles for themselves and form their own impression.

A major aspect of choosing the ‘many workspacdes’ pattern is the need to have different views or task “modes” available at the same time (Tidwell, 2010).

“Side-by-side comparisons between two or more items can help people learn and gain insight. Let users pull up pages or documents side-by-side without having to laboriously switch context from one to another.” – Tidwell (2010)

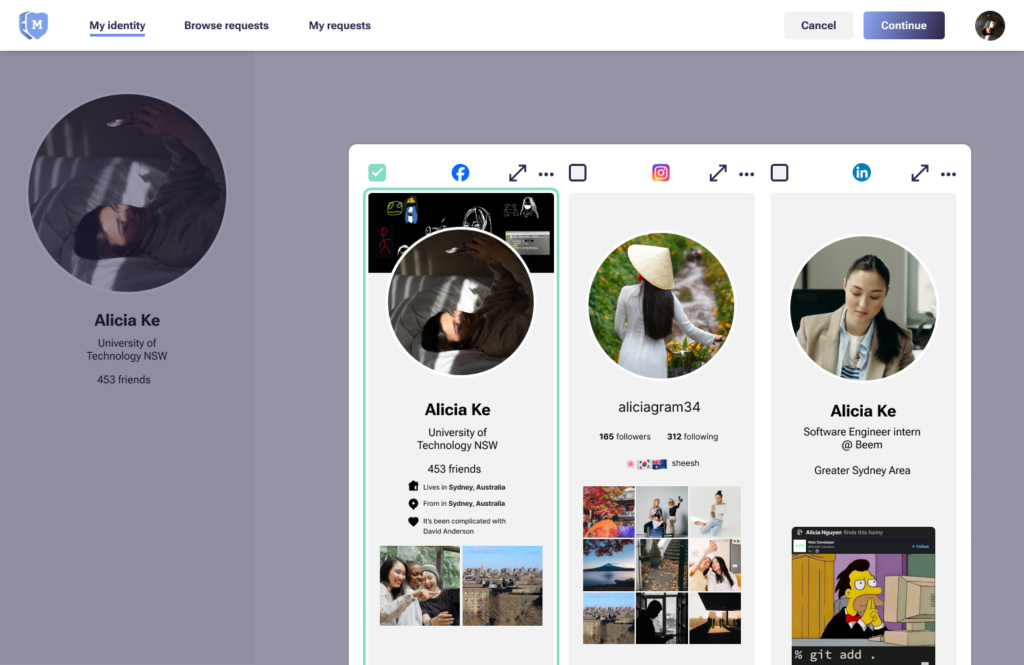

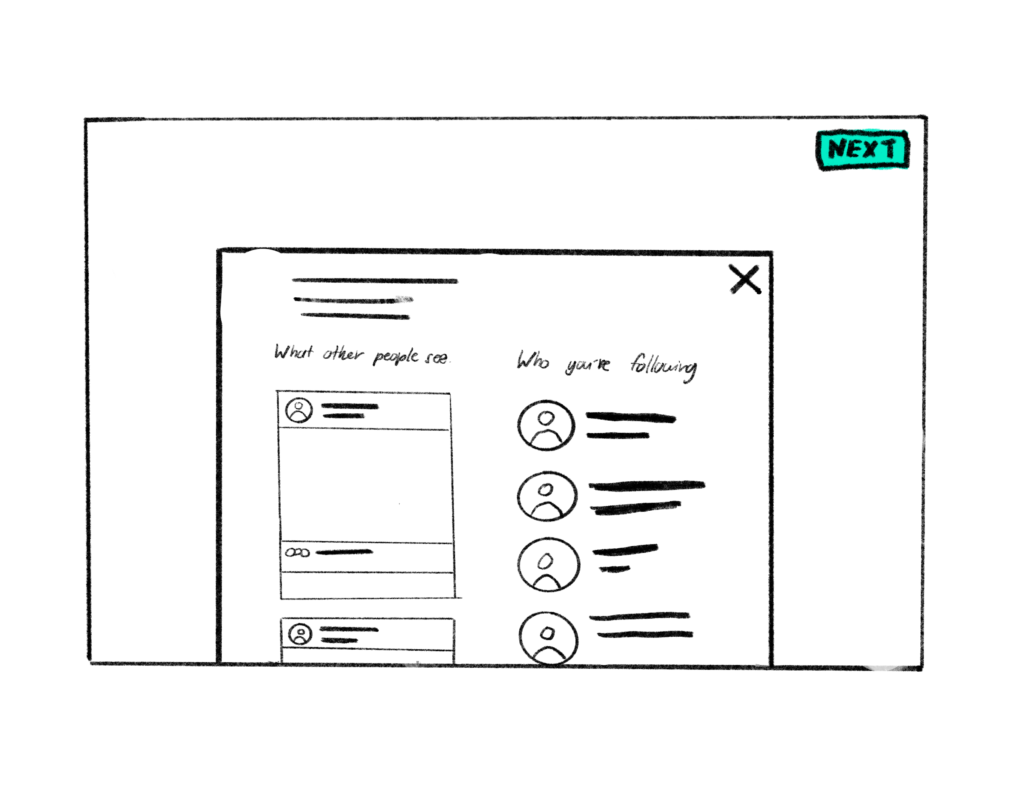

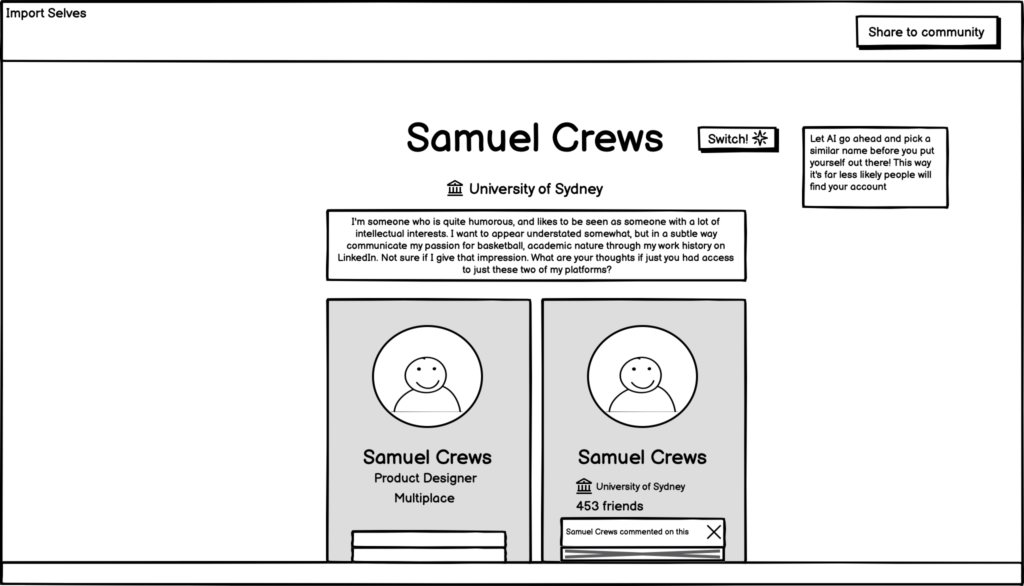

Improving ‘Share to community’ function

Multiplace would include a community function where users can share a combination of their profiles to certain publics and get feedback about the impression they are giving others. Getting the opinion of others can provide more accurate and reliable feedback about the kind of image one projects.

The first iteration involved a single share option, which sent all of one’s identities to the public (Figure 7). However, the next iteration would allow users to select a certain combination of profilesto share, so that they can better understand the impression that someone who can view the selected profiles holds of them (Figure 8). Some audiences may not have access to all of one’s profiles, as they may be part of the users professional audience and only have access to public profiles such as LinkedIn and Facebook. People closer to the user may see their WhatsApp activity and private Instagram posts. Depending on the assortment of profiles shared, users can get feedback how a particular audience or individual may perceive one’s profile.

The second iteration adds navigation features, particularly the header with the ‘Next’, ‘Share’ and‘Share to Community’ options which are visible in the appendix, as well as minor updates like AIfeatures to switch out certain aspects of one’s identity (such as their real name, see Figure 9) with similar attributes to maintain privacy when sharing to the real world.

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Wireflow for this component

https://www.figma.com/file/gzJcF39qbWwb0Q3Uj8HPqF/Wireflow-A2?type=whiteboard&node-id=0%3A1&t=CnTyeMsJUYjZHImB-1

Iteration 2/3: Wireframes -> Mid-fidelity

Stacking Identities to save clicks

It was noticeable during the usability evaluations that the process of adding social media profiles was quite tedious. Whilst there were limited comments from participants, the extra click of the right arrow in order to move to the next profile each time a user added an identity was very apparent. In some tests, users continued to click the right arrow even after all of the social media profiles were translated onto the prototype, potentially due to the visibility of unlimited empty boxes on the right, asking to be filled out.

To improve this experience, empty profiles were removed to avoid confusion and mindless clicking and instead, profiles are only added as the user searches for and finds their own. This would reduce the unnecessary step of clicking and provide a clearer view.

‘Continue’ button placement

The wireframe included a header with a main call to action (CTA) button which existed throughout every screen of the prototype. This header was kept in every screen for consistency, and served to guide users to the next main function at any stage or screen of the product.

For the first stage of this product, where users place the links to their social media accounts onto Multiplace, the content on this CTA button ‘Next’ was ambiguous. Users were unsure as to whether clicking it would proceed them to add the next ‘self’ or social media profile, or whether it meant the users were done adding profiles and were ready to progress to the next stage. The button content was changed to ‘Continue’ as a result.

Two users also mentioned that they preferred that it be located at the bottom, consistent with the conceptual models of common forms found throughout registration pages.

Hovering and selectability

Many users were not immediately aware that identity columns were selectable after clicking the ‘Share’ button. It became clear once they had selected a column and it would be highlighted, suggesting selection. To address this, a hover animation was added when the user passed their cursor over the identity columns prior to being clicked.

Quicker editing, less clicks

When assigned with making edits in a particular profile or ‘identity column’, some users attempted to make edits by directly clicking on the particular aspect of their profile they wanted to change from the Home screen.

This was entirely non-verbal, as users clicked once or twice on their LinkedIn post engagement, attempting to make the change before quickly noticing the edit icon visible above each identity column which would open the modal and allow editing.

This subtle behaviour suggested that users understand the change they want to make and implement as soon and as easily as possible. As the purpose of Multiplace involves managing one’s online identity (an activity which demands constant editing and adjustment of one’s profiles online) there is value in allowing users to quickly make changes instead of making it a two-step process.

Iteration 3/3: Wireframes -> Mid-fidelity

A ‘Sharing’ mode

If users did click the Share button, there was very little feedback about the next step. Users woulddiscern that they could begin selecting ‘identity columns’ due to the hover animations added inthe previous iteration, but that involved moving their cursor over the columns. Until then, therewas no visible change to the system status.

To improve this and communicate to users that it is time to begin sharing, everything leave the identity columns and header were greyed out. This way, there was feedback upon clicking ‘Share’. The columns would become highlighted if the cursor was moved over them, prompting users to click and select them.

When to click ‘Share’?

There was a subtle disparity between the mental model of some users and our conceptual model for sharing in both rounds of testing. The ‘Share’ button on the right of the header would initiate a sharing process, which some users discerned. For others however, they felt that the ‘Share’ button was the final action, and they needed to select their profiles for sharing before they clicked it, and therefore hesitated to click it initially. Instead, they clicked the identity columns and tried to find a way to select these profiles.

To improve this, we took inspiration from the android gallery and similar photo applications which enable users to select items before deciding the course of action (share, delete, move etc). Weadded check boxes which allow for the selection of columns, so that users can select before sharing. We also preserved the existing model if a user preferred it.

Hover editing

Since the option to make edits directly from the Home screen was implemented, further testing suggested that this could be communicated even better. Despite the large number of edit icons visible throuhgout each identity column (which many users utilised), some users still appeared to seek for a method of editing their profiles.

By signifying the affordance of editing, there is an opportunity to communicate and encourage users to make edits in their profiles directly. By hovering over images and text, a shift in appearance suggest that these items can be edited.

Deliver